The Standard Terraform and OpenTofu Files + Their Uses

By Matt Gowie

Table of Contents

If you’ve hopped between different Terraform or OpenTofu (collectively referred to as TF going forward in this post) projects across teams, you’ve definitely seen this problem: everyone organizes their TF files differently. Some teams jam everything into a single main.tf file, while others scatter resources across dozens of specialized files. This isn’t just an aesthetic issue — it creates real headaches when you’re trying to understand or fix infrastructure code.

When you join a new project, your first days often aren’t spent making useful changes. Instead, you’re decoding how this particular team decided to organize their TF code. Even worse, within a single codebase, different contributors frequently follow completely different organizational patterns, creating a confusing patchwork that slows everyone down.

At Masterpoint, we standardized our TF file organization after seeing firsthand how consistent structure drastically improves collaboration. Well-organized TF projects make onboarding faster, reduce errors, and simplify maintenance and troubleshooting. When the files that make up a TF project have standard names, locations and meanings, you know exactly where to look when something needs changing.

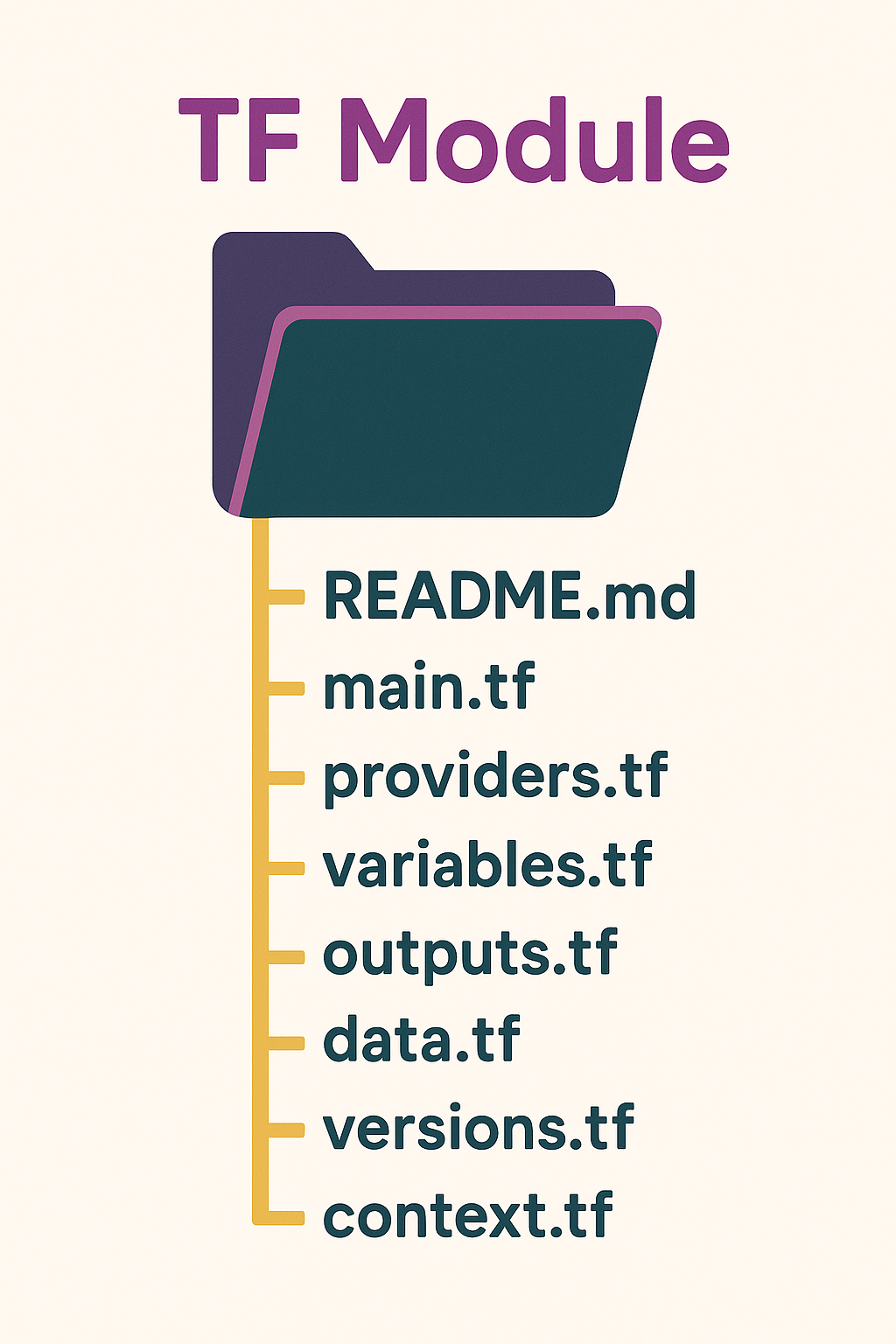

This guide walks through the TF files you’ll see in well-structured projects, what belongs in each one, and why this organization actually matters. We’ll use an example of an AWS VPC, but the principles apply to any TF managed infrastructure. We’ll cover the core files like main.tf, variables.tf, and outputs.tf, plus supporting files like providers.tf and the often overlooked .terraform.lock.hcl. Beyond the files themselves, we’ll also dig into practical conventions and patterns that keep your infrastructure code clean and maintainable.

Core Configuration Files

main.tf: Resource Definitions and Primary Infrastructure

Every TF project needs a main file (it doesn’t technically need to be named main.tf but that is the industry convention). This file defines the actual infrastructure resources you’re provisioning. When someone first looks at a TF project, they’ll typically start here to understand what you’re building.

Before we go further, let’s clarify some basic terminology. A TF project refers to your entire infrastructure codebase: everything in your repository including root modules, child modules, and supporting files. A TF module (root module or child module) is a standalone, reusable collection of TF files that encapsulates specific functionality and can be used independently or consumed by other configurations. You might use a VPC module, an RDS module, and an ECS module within your project, but each module exists as its own complete unit.

The main.tf file should contain your core resource definitions without getting bogged down with variables, outputs, or provider configurations. For an AWS VPC module, you’d include resources like VPCs, subnets, route tables, and internet gateways here.

If you find yourself breaking main.tf into multiple service-specific files like ec2.tf and rds.tf, you might be building what we call a “terralith” - a monolithic Terraform configuration that tries to do too much at once. Instead, consider breaking your infrastructure into smaller, focused child and root modules that each handle a specific component.

Here’s an example of a main.tf file:

resource "aws_vpc" "this" {

cidr_block = var.vpc_cidr

enable_dns_hostnames = true

tags = merge(var.tags, { Name = "${var.namespace}-vpc" })

}

resource "aws_subnet" "public" {

count = length(var.availability_zones)

vpc_id = aws_vpc.this.id

cidr_block = local.public_subnet_cidr_blocks[count.index]

availability_zone = var.availability_zones[count.index]

}

This main.tf example focuses on what matters: the core infrastructure resources that make up your VPC. It doesn’t try to handle everything from IAM policies to application servers, just the specific resources needed for this module’s purpose.

variables.tf: Input Variable Declarations

The variables.tf file is where you declare every input parameter your Terraform module accepts. Having a dedicated file for this purpose makes it obvious what values can be provided when someone uses this code.

When setting up your variables, group related ones together and maintain consistent naming conventions. Use snake_case for variable names (like vpc_cidr rather than vpcCidr) to match TF best practices. Each variable should include:

- a description that explains what it’s for

- appropriate type constraints

- validation rules, if needed to ensure specific input values

Here’s an excerpt of a variables.tf file:

variable "vpc_cidr" {

description = "VPC CIDR block"

type = string

default = "10.0.0.0/16"

validation {

condition = can(cidrnetmask(var.vpc_cidr))

error_message = "The vpc_cidr must be a valid CIDR block."

}

}

Provide default values for non-critical variables wherever a default makes sense. On the other hand, require explicit input for customization of the infrastructure. For example, a default CIDR for a VPC might be reasonable, but resource names or a connected ALB ID don’t have sensible default values and should be required.

Variable validation prevents runtime errors by checking values and failing during the plan phase with helpful error messages. This is particularly useful when working with specific formats like CIDRs, as above, or ensuring values fall within acceptable ranges for your resources. We have plenty of examples of variable validation in our module here.

outputs.tf: Exporting Values

The outputs.tf file defines exports, which are values that will be visible and returned from your child or root module. Well-structured outputs make your modules reusable and composable by exposing important resource attributes.

Make sure you put a description on each output value, as this helps a reader understand it.

When naming outputs, follow a consistent pattern that makes the purpose clear. Prefix output names with the resource type they relate to, and use descriptive suffixes that indicate what attribute is being exposed. For example, vpc_id is clearer than just id and private_subnet_ids is clearer than subnet_ids when you’re specifically outputting private subnet IDs.

Here’s an excerpt of an outputs.tf file.

output "vpc_id" {

description = "VPC ID"

value = aws_vpc.this.id

}

output "public_subnet_ids" {

description = "List of public subnet IDs"

value = aws_subnet.public[*].id

}

output "private_subnet_ids" {

description = "List of private subnet IDs"

value = aws_subnet.private[*].id

}

Only create outputs for values that you need access to or that other modules might reasonably need. Common examples include resource IDs, ARNs, generated names, and connection information. Avoid exposing internal implementation details that shouldn’t influence how other modules interact with yours, such as the actual CIDR range of a private subnet.

Well-crafted outputs are a contract between your module and its consumers, defining exactly what information is available after your infrastructure is provisioned. Like any good API contract, this means you should maintain backwards compatibility whenever possible. Adding new outputs is generally safe, but removing or changing existing outputs can break configurations that depend on them.

When you do need to make breaking changes to outputs, version your modules and communicate the changes clearly. This allows consumers to upgrade on their own timeline rather than having their infrastructure builds suddenly fail.

data.tf: External Data Source Queries

data.tf is an optional file that centralizes data source declarations. These are configurations that fetch information from your providers or external systems rather than managing resources. Think of data sources as read-only references to existing infrastructure.

Common data sources retrieve information such as:

- AMI IDs

- existing VPC attributes or IDs

- IAM policy details

Centralizing these in data.tf makes it easy to see what external data, if any, your module depends on.

Here’s an example of a data.tf file

data "aws_ami" "amazon_linux" {

most_recent = true

owners = ["amazon"]

filter {

name = "name"

values = ["amzn2-ami-hvm-*-x86_64-gp2"]

}

}

data "aws_availability_zones" "available" {

state = "available"

}

While centralizing data sources in data.tf is generally a good practice for visibility, it’s not always the most practical approach for very simple cases. For instance, if a module uses only a single data source (like one that looks up the current AWS Account ID), keeping it in main.tf or directly alongside the resource it supports can make more sense for immediate context. However, once you start using two or more data sources in a module, especially if they retrieve related information like VPC and subnet details, it’s best to group them all into a dedicated data.tf file. This keeps simple configurations lean and ensures that more complex sets of data dependencies are well-organized and easy to find.

checks.tf: Resource-Level Validation and Policies

A standards-driven TF project often includes an optional checks.tf file that centralizes your validation rules and assertions. While validation blocks in variables.tf verify input values, checks.tf focuses on validating the actual infrastructure configuration and enforcing organizational policies. See our full article on the check block here.

The checks.tf file uses TF’s built-in validation framework to define conditions that must be met for the configuration to be considered valid. These validations run during the plan phase, catching potential issues before they reach your production environment.

Here’s an example of a checks.tf file:

check "s3_encryption" {

assert {

condition = alltrue([

for bucket in aws_s3_bucket.logs :

bucket.server_side_encryption_configuration[0].rule[0].apply_server_side_encryption_by_default[0].sse_algorithm == "AES256"

])

error_message = "All S3 buckets must have server-side encryption enabled with AES256."

}

}

A key advantage of using checks.tf is that it separates these broad validation assertions from individual resource definitions. This means anyone reviewing the code can quickly understand the global conditions and standards being enforced across the configuration, without needing to inspect each resource. Such checks establish a consistent set of guardrails, helping to prevent accidental misconfigurations or deviations from your intended infrastructure design.

imports.tf: Resource Import Declarations

When you need to manage existing infrastructure with TF, one of the first steps is bringing those current resources into your TF state. The imports.tf file, which uses import blocks (available since Terraform v1.5), offers a clear and manageable way to do this. It’s a more structured approach compared to the older imperative terraform import command-line operation, making the process more transparent and automatable.

Instead of relying on CLI commands, you define import blocks directly in your TF configuration files. While these can be placed in any .tf file, organizing them in a dedicated imports.tf is a common practice. Each import block identifies an existing piece of infrastructure and assigns it a TF resource address. Using this approach means your import process is documented in code, making it reviewable by your team, captured in your git history, and consistently repeatable across many instances of that root module.

Here’s an example of a imports.tf file:

# Example in imports.tf

import {

to = aws_s3_bucket.legacy_logs # The address Terraform will use for this S3 bucket

id = "company-logs-bucket" # The S3 bucket's actual name in AWS

}

import {

to = aws_iam_role.existing_lambda_role

id = "lambda-execution-role" # The IAM role's name in AWS

}

Using a distinct imports.tf file immediately clarifies which parts of your infrastructure were adopted by TF, rather than provisioned by it. This clarity is valuable for infrastructure audits and simplifies knowledge transfer when team members are getting acquainted with the project.

If you’re migrating a large, existing system to TF incrementally, these import blocks, and the corresponding HCL you develop, effectively chart your progress.

Want to know more about importing resources in TF? Our article on breaking up Terraliths talks through this topic a good bit.

Supporting Configuration Files

The previous files are extremely common across most TF projects we see and focus on your infrastructure. Let’s look at other supporting types of files which connect your infrastructure to external services.

providers.tf: Managing Provider Configurations

The providers.tf file centralizes all your TF provider configurations in one place. Providers are plugins that Terraform uses to interact with cloud platforms, services, and APIs. By isolating these configurations, you make it easier to understand which external services your module is interacting with.

Here’s an example providers.tf file:

provider "aws" {

region = var.aws_region

assume_role {

role_arn = var.deployment_role_arn

}

default_tags {

tags = var.default_tags

}

}

provider "aws" {

alias = "us-west-2"

region = "us-west-2"

}

Provider configurations often handle authentication methods, region settings, and default parameters. Having these in a dedicated file makes it simple to update authentication approaches or other shared settings across your entire project.

When multiple configurations of the same provider are needed, such as deploying resources across different AWS regions, the alias parameter distinguishes between them. These aliased providers can then be referenced in resource blocks throughout your configuration. In the example above, the second provider can be referenced as aws.us-west-2 in your resources.

versions.tf: Terraform and Provider Requirements

While providers.tf configures how TF interacts with external services such as cloud providers, versions.tf defines what versions of TF and those providers are compatible with your code. This distinction helps manage compatibility at both the tool level and the API level.

Here’s an example versions.tf file:

terraform {

required_version = ">= 1.3.0, < 2.0.0"

required_providers {

aws = {

source = "hashicorp/aws"

version = ">= 4.16"

}

random = {

source = "hashicorp/random"

version = ">= 3.4.3"

}

}

}

The required_version argument ensures your configuration runs with a compatible TF version and fails if none are available. This prevents mysterious errors when teammates use different versions. At Masterpoint, for child modules (reusable modules that are called by other TF configurations), we specify a minimum version that supports the features we need.

The required_providers block serves two important functions:

- where TF should download providers from

- what version constraints apply

The source attribute is particularly important in organizations that use private provider registries or forks of official providers.

Want to know all about versioning in Terraform and OpenTofu? Read our definitive article on that topic: The Ultimate Terraform Versioning Guide.

.terraform.lock.hcl: The Dependency Lock File

The .terraform.lock.hcl file is often overlooked, but it’s important as it helps ensure consistent builds across environments. Unlike the previous files which you create manually, TF automatically generates and updates this lock file when you run terraform init. This file should only be used in root modules – child modules should not have lock files.

Here’s an example .terraform.lock.hcl file:

# This file is maintained automatically by "terraform init".

# Manual edits may be lost in future updates.

provider "registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/aws" {

version = "4.16.0"

constraints = "~> 4.16"

hashes = [

"h1:6V8jLqXdtHjCkMIuxg77BrTVchqpaRK1UUYeTuXDPmE=",

"zh:0aa204fead7c431796386cc9e73ccda9a7011cc33017e9338c94b547f30b6f5d",

# Additional hash values omitted for brevity

]

}

The lock file records the exact versions and content hashes of each provider binary used in your project. This ensures that everyone working on the project and all deployment environments use identical provider implementations, preventing “works on my machine” problems caused by subtle provider differences.

Beyond consistency, the lock file provides security benefits by protecting against supply chain attacks. The cryptographic hashes verify that the provider binaries haven’t been tampered with between downloads. If someone compromises a provider repository and injects malicious code, the hash mismatch will cause TF to reject the corrupted binary.

Like package-lock files in other ecosystems, the .terraform.lock.hcl file should be committed to version control. This shared record enables consistent infrastructure deployments across development, testing, and production environments.

When new team members clone your repository, the lock file guarantees they’ll use exactly the same provider versions during local development. Similarly, your CI/CD pipelines can rely on these locked dependencies for reproducible deployments.

If you need to update providers to newer versions, the terraform init -upgrade command will refresh the lock file with the latest versions that satisfy the constraints in versions.tf.

If your team works on multiple operating systems, use the following command whenever creating or updating your lock file:

terraform providers lock -platform=linux_amd64 -platform=darwin_arm64 -platform=windows_amd64

This ensures that the .terraform.lock.hcl file includes dependency checksums for multiple target platforms, preventing errors during terraform init or terraform plan on system architectures other than the one that generated the lock file. Without this, teammates using different operating systems will encounter checksum mismatches or be unable to use the lock file reliably.

Advanced TF File Usage

You’ve learned about standard TF files for your infrastructure and supporting services. Let’s look at some advanced features.

Locals and Their Placement

Local values (or “locals”) help simplify your TF configurations by assigning names to expressions. While technically you can place locals anywhere, following a consistent pattern improves readability and maintenance.

For smaller projects, a single locals block at the top of the main.tf file works well. This approach keeps derived values visible and accessible to all resources.

Here’s an excerpt showing this:

locals {

public_subnet_cidr_blocks = [

for i in range(length(var.availability_zones)) :

cidrsubnet(var.vpc_cidr, 8, i)

]

private_subnet_cidr_blocks = [

for i in range(length(var.availability_zones)) :

cidrsubnet(var.vpc_cidr, 8, i + length(var.availability_zones))

]

}

Keep locals close to where they’re used.

Avoid scattering multiple locals blocks throughout a file. Doing so creates a treasure hunt for anyone trying to understand how values are derived.

Instead, aim for a single, well-organized block that groups related transformations together with clear names and comments when needed. Want to see an example of some intense locals logic in TF that is well organized and commented? Check out our terraform-spacelift-automation open source module’s main.tf and your eyes will go wide.

When to Create Additional .tf Files

While we’ve covered the standard files found in most TF projects, you may occasionally need to create additional files for specific purposes. The key is distinguishing between helpful organization and the warning signs of a “terralith”: a monolithic TF configuration that tries to do too much in one place.

Additional files make sense when they group related resources that form a logical component of your infrastructure. For example, in a complex networking module, you might keep your route tables in route_tables.tf and your network ACLs in nacls.tf, even though both technically contain networking resources that could belong in main.tf.

├── main.tf # Primary resources (VPC, subnets)

├── route_tables.tf # Route tables and routes

├── nacls.tf # Network ACLs and rules

├── variables.tf

└── outputs.tf

What doesn’t make sense is creating separate files for different AWS services when they’re not actually related or serving a cohesive purpose. If you find yourself creating files like s3.tf, rds.tf, and lambda.tf within the same module, ask yourself: do these resources work together toward a single goal, or are they separate systems that just happen to be deployed together?

If you’re routinely adding new .tf files to an existing module, it’s often a sign that your module’s scope has grown too large. Instead of continuing to add files, consider whether you should extract some functionality into separate modules.

For example, a web application module that includes RDS for the app database, an ALB for traffic distribution, and ECS for compute makes sense as one module - these resources work together to deliver the application. But if your module provisions an S3 bucket for file storage, an RDS database for a different application, and Lambda functions for unrelated data processing, these are separate concerns that should be split into focused, root modules.

Each module should do one thing well.

Using context.tf for Project Metadata

A lesser-known but valuable pattern in TF projects is using the context.tf file to provide standardized metadata and tagging. This approach, popularized by the Cloud Posse terraform-null-label module, ensures consistent naming + tagging across all your infrastructure resources.

The context.tf file typically contains a module reference that standardizes tags, naming conventions, and other cross-cutting concerns:

module "this" {

source = "cloudposse/label/null"

version = "0.25.0"

namespace = var.namespace

environment = var.environment

stage = var.stage

name = var.name

attributes = var.attributes

tags = var.tags

}

This approach creates a standardized “context” object that gets passed to all your resources, ensuring consistent naming and tagging. For organizations managing dozens or hundreds of Terraform modules, this consistency is invaluable.

The real power comes when you combine this with provider-level default tags. For example, in AWS, you can define organization-wide tags in your providers.tf, then supplement them with resource-specific tags in each resource:

# In providers.tf

provider "aws" {

default_tags {

tags = {

Organization = "Masterpoint"

ManagedBy = "Terraform"

}

}

}

# In main.tf

resource "aws_vpc" "this" {

cidr_block = var.vpc_cidr

tags = module.this.tags

}

The context pattern vastly simplifies compliance with organizational tagging policies. Rather than implementing tagging logic in each module, you can standardize it once in context.tf and reuse it everywhere.

Additionally, having this metadata consistently available means you can generate outputs that follow standard naming patterns, making it easier to lookup information between modules.

We’ve written extensively on the null-label pattern and we’d encourage you to adopt this to improve your projects’ maintainability. You can read the basics in our introduction post and read more about utilizing context.tf in our follow up advanced post.

Conclusion

Organizing your TF files in a consistent, logical manner is key to creating a shared understanding across your team, making the codebase more approachable and predictable. When every file has a clear purpose, platform developers can navigate your infrastructure code with confidence, knowing exactly where to find specific configurations or make changes.

The benefits of this standardization compound over time. New team members onboard faster with consistent patterns. Troubleshooting is easier when you know exactly where to look. Code reviews go smoothly since reviewers can focus on actual changes rather than deciphering organization schemes.

Separating variables, outputs, data sources, and resources into their own files might seem like a minor detail or tedious chore. But infrastructure code is read and modified far more often than it’s initially written. A few minutes spent organizing your files today saves hours of confusion three months from now.

You don’t have to do this all at once. Start applying these patterns incrementally on existing projects. With new modules, begin with the right structure from day one. Proper organization naturally guides developers toward other best practices like single-responsibility modules and clean interfaces.

At Masterpoint, we’ve seen how standardizing TF file organization has streamlined collaboration, reduced mistakes, and maintained quality as we’ve grown and helped our clients grow. These aren’t just theoretical benefits; they translate directly into faster delivery and more reliable infrastructure.

👋 If your team is struggling with inconsistent Terraform organization or looking to establish better practices for Infrastructure as Code, we'd love to help. To discuss how we can support your infrastructure goals with proven patterns and strategies, get in touch!